Objects of Desire

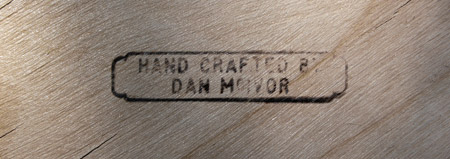

'Bowl', c. 1999. Dan McIvor.

I spend a lot of time reading design magazines, books, and blogs; graphic design, industrial design, architecture, interaction design – all manner of producing things and places of style, of expression, and for use by people. It’s a very convenient confluence of professional, academic, and personal interest – I’m a very lucky person because I enjoy it a lot.

But as a complaint (what?), it seems that any designers (but not all, and seemingly less all the time) spend a lot of time creating things without any regard for meaning beyond the object’s significance within the particular design field’s traditions. I know, I know. I talk about ‘meaning’ a lot, but it’s what seems to matter to me these days.

For instance, van der Rohe’s Barcelona Chair is judged not by its ‘physical definitions’ – the various dimensions, ornaments, characteristics, and materials that define it as part of a regionally-specific culture, but rather how it fit within/reacted to the traditions of contemporary, urban furniture design. So, yes, dimensions, ornaments (or lack thereof), characteristics and materials all figure very importantly, but not at all as a function of some larger, deeper regional culture. There is no ‘place’ where this chair makes sense or has any real meaning. It is an object, arguably ‘outside’ any context. (I say ‘arguably’ because the chair was indeed conceived as a part of a larger showcase of early 20th century German design and industrial prowess, but yet its neutral form and function has since made it an ‘international’ object. Does that mean it no longer has any meaning?)

Having written that, I’m immediately struck by/reminded of two things: 1. the chair indeed has a meaningful, nameable context – its ‘specific culture’ is that very real culture and society of the particular design field, and then; 2. design cultures have no ‘place’ themselves but rather is a transcendent community of shared ideals, characteristics, and traditions. When I say transcendent, I mean the design cultures exist ‘above’ or ‘outside’ the physical boundaries that have typically defined a society or culture. As such, design culture is a glowing example of McLuhan’s concept of ‘global village’, made immaterial and transcendent by its lack of physical place.

I wonder if there is a danger in removing or ignoring the physical definitions from the objects around us. I find that I’m sensitive to how physical connections to people and places add layers of substance to an object or space (read my previous post), and how those layers can alter how we perceive the ‘style’, interpret the ‘expression’, and prefer the ‘use’ of a thing or space.

Consider the bowl up there. I can practically ‘list’ the layers on that thing: 1. made by hand; 2. by my wife’s great-uncle, the late Dan McIvor; 3. who is a Member of the Order of Canada and in Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame for inventing the modern water-bomber by retrofitting retired Martin Mars aircraft (among other things — I consider this to be a separate layer beyond the simple fact of familial relation); 4. made for our wedding, ; 5. made from wood from his backyard (don’t ask me what it is) in Kelowna, British Columbia. Irrespective of these layers and considering it as a ‘transcendent’ object, the bowl is merely okay – it has a sort of pragmatic form to it, which is nice. But considering these layers, the bowl takes on all kinds of depth that attracts me to it and makes it ‘present’ to me – I use it with intention because it was made with intention. I use it knowing where it came from and why. Even if I had a Marc Newson designed bowl, I would still prefer to use McIvor’s bowl.

It seems to me that there is always an opportunity for creating objects that sit somewhere within the threshold between the ‘transcendent’ and the ‘present’, between good style and regional meaning. Not that this doesn’t happen – in fact, it would be accurate to say that most good architecture and some graphic design works within this threshold. But from what I can tell, the same couldn’t be said of industrial design (objects usually designed for univeral function and appeal) and interaction design (interfaces usually designed for universal function and appeal).

I spend my idle moments thinking about this in relation to public objects and spaces here in Thunder Bay. It’s idle thought, so nothing useful has taken root. It usually happens when I’m driving through the intercity area, between Fort William and Port Arthur where the malls and box stores are. These are spaces that are intentionally devoid of any specific character – except as uniform store-fronts, as expendable and forgettable as their contents. I also see the need for this design threshold locally when I look at locally produced graphic design, which defers to some placeless ideal – a set of characteristics developed somewhere else. Technically, the bigger offices do a good job, but that’s where it ends. I think soon I’ll do a post on the City of Thunder Bay’s new online livery, which will nicely illustrate my point. (Don’t get me started on local web design, which doesn’t appeal to or satisfy anything.)

However, the little barrier I constantly bang into when considering this threshold in regional terms is this: how does a regional style emerge? I would like to be able to put it together myself, or at least my ‘interpretation’ of what it should be, but I feel that as soon as I start with such deliberate intention, it is no longer ‘genuine’ or ‘authentic’. That of course reminds me that the idea of ‘genuine’ or ‘authentic’ is something of a lie to begin with, a function of nostalgia and romance. I’m paralyzed, it seems, by this circle of ridiculous analysis.

I guess I’ll just have to design something, sideways.